TENDING THE FLAMES

Discovering tiny miracles while living and cooking in an unhoused encampment

By Mahnaz Saberi, in conversation with Amelia Rayno

Photos by Colin Peck and Amelia Rayno

This story was originally published in Meal Magazine Vol. 3

If you enjoy it, please consider ordering the print issue, or subscribing via Patreon.

A note from the journalist:

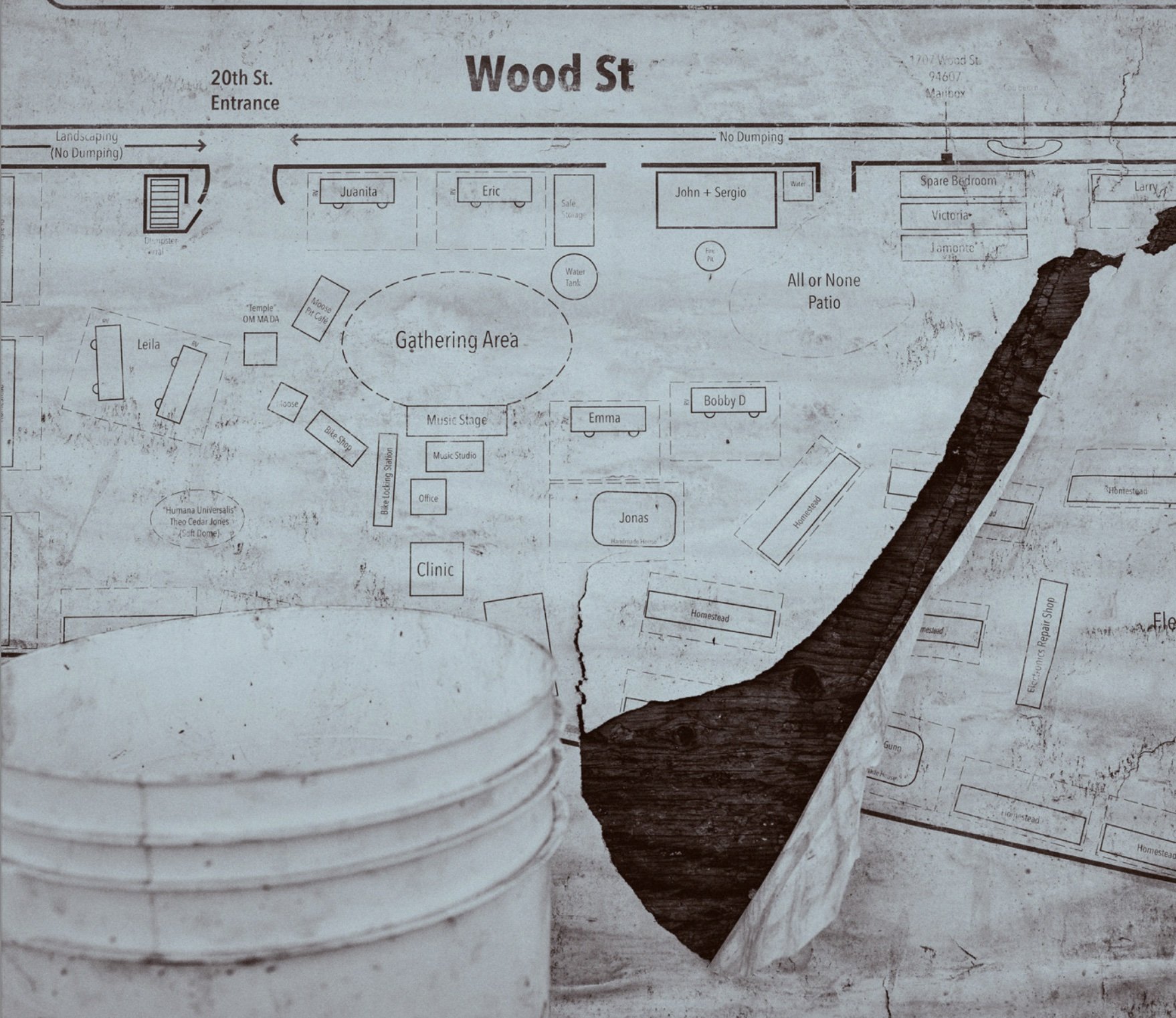

In July of 2021, I arrived at Wood Street, a sprawling unhoused encampment in West Oakland, California, where I planned to spend a week or so documenting the lives of those living in RVs, trailers, and improvised structures on the dirt lots that abut the I-880 overpasses and extend beneath them. Galvanized by the depth of stories and capacity of strength by the individuals I was fortunate to develop intimate relationships with, I wound up staying for nearly four months, parking my camper-outfitted cargo van inside one of the lots, and experiencing daily life, as well as regular crises, along with my neighbors.

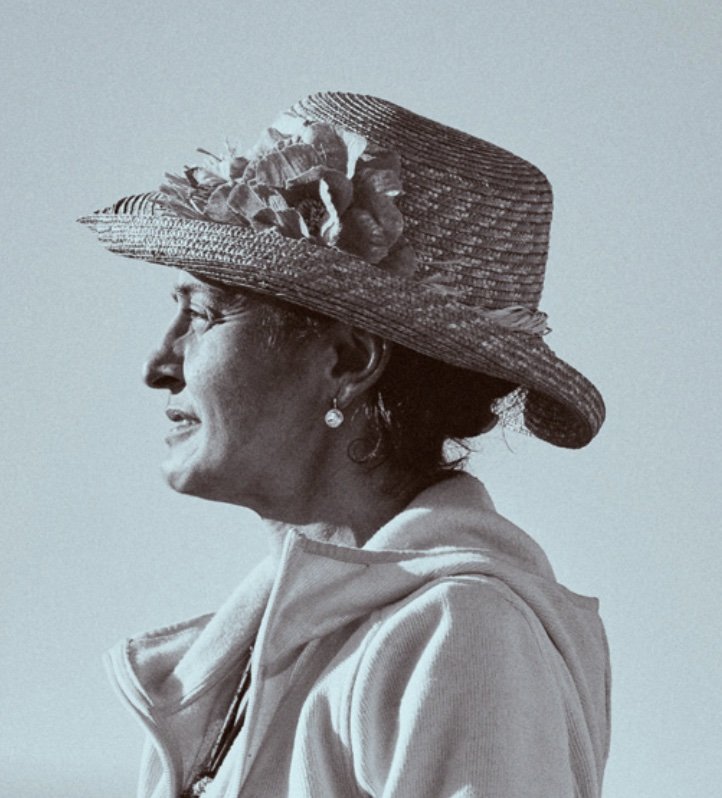

It was there I met Mahnaz (47), a woman who immediately struck me as charming, creative, resourceful, and incredibly tough. We shared a lot of food and a lot of conversations, moments which inspired the following story.

Throughout the course of this collaboration, which lasted another four months, we spent dozens of hours talking about her past and her present, and a few hundred more hours forming a narrative together, often editing for four or five-hour stints that extended into the middle of the night. We worked hard to maintain her voice and sentiments. This is only part of the story of Naz, and what we cut from it could inspire its own book—but I believe what remains is a compelling account that will challenge how readers think of unhoused individuals, and perhaps life itself.

— Amelia Rayno

And for my next near-miracle, I’m going to make tahdig.

The perfect escort to Persian rice, tahdig is the thin crust made at the bottom of the pan using yogurt, egg and saffron; familiar staples that conjure so many memories of my youth.

Of course I don’t have all of those ingredients right now. You rarely have everything. Without the convenience of expendable cash, you might not always find saffron—or even rice—but sometimes, you find hope instead. And sometimes that hope comes in the form of about four pounds of mac n’ cheese.

I picked it up from one of the local barbecue restaurants the other day; leftovers up for grabs as they were closing. I piled the aluminum trays onto my collapsible wagon and wheeled them back down Wood Street. Bringing anything back in this fashion requires skilled navigation. This road at the edge of West Oakland, lined with old warehouses and unhoused camps, has more potholes than any other I’ve seen in my life. They carve out the sides of the defunct Southern Pacific railways that cut through crumbling pavement.

Back before the Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge were built, before San Francisco became a metropolis, this was the end of the line. For migrating families, it was a new horizon of freedom. Many, who were fleeing oppression, found dignity here; the chance to make their own way. It was the last stop on the tracks, but the first stop for hope.

In some ways, it still is.

About ten years ago, people without traditional houses began setting up homesteads made from RVs, trailers and found materials on land that now has a patchwork of ownership (the largest portions belonging to the City of Oakland, California Transportation, and the federal railroads). The authorities have often let one occupation continue for a year or so before pushing everyone out, leaving a trail of cherished possessions in their wake.

The lots, which are still often treated as an informal junkyard for outsiders, are dappled with small mounds formed by illegally dumped toxic dirt, and heaps of personal belongings that now sprout with pampas grasses and wild fennel. Some may see this area as a dead end. But it’s in this imperfect, unconventional place that I am learning how to carve a new path where there was none before. One of my mottos for Wood Street and for myself are the same:

“Please pardon the dust and debris during our reconstruction, we’re working on a better tomorrow.”

Sometimes you’ve got to make a mess before you can get cleaned up. Sometimes you need to get back to survival, to reconcile the old version of you with the one that will never be the same. Sometimes you just need to cook, and to eat.

To create tahdig, you have to master the art of patience.

In Iran, the presentation of your rice is everything. If your grains are broken or sticky, you’ve failed. Rather, each must be separate, glistening and wafting with the aroma of the rose water that’s poured over the top while they cook. If your rice didn’t come out right, it’s most likely your tahdig didn’t either, and vice versa.

This art often takes a lifetime to perfect.

I remember when my mother began teaching me how to create the perfect vat of rice. I joked, then, that I wouldn’t need to know how; that I was going to be a modern woman. Little did I know it would be a skill I would draw on so enthusiastically later in life.

My father came to the U.S. first with an educational visa and a scholarship to complete his PhD in philosophy. The plan was for him to return to Iran afterwards, and become a professor at the University of Tehran, where he had gotten three previous degrees. Immigrating to the United States with his family was never part of it.

Then came 1979. Angry that the U.S. military was supplying Iraq with weapons in its fight against Iran, and wanting to extinguish the exploitative oil relationship with the Western power, a group of militarized college students that supported the Iranian Revolution took over the U.S. Embassy and seized hostages. Among them were some of my dad’s graduate fellows at the University of Tehran. When they contacted him to let him know of their plans, he quickly called my mom. He understood their indignation, but was deeply wary of the religious regimes that the Revolution would later bring to power—and with them, the profound suppression of personal freedoms.

“Grab the babies, pack what you can and get on the first flight to the States,” he told Mom. “Tell everyone you know: the country is about to go back 200 years.”

At just 22 years old, my mom was scared to abandon her family and all that she knew. But heeding my dad’s warnings, she did; my brother Masoud (at age 3) and me (age 4) in tow. We got out just before the embargo, after which no one could leave. One of the things my mom packed amidst our limited luggage was her rice strainer.

First, you have to light the stove.

Really, it’s a small smoker drum. My partner, Jeffrey, cut a hole in the roof of the trailer where we live and attached some exhaust pipes to make a chimney for it.

The stove is stationed on the left wall of the trailer, propped up with a metal crate. At the trailer opening, a countertop is usually covered in food items, electronics, and other goods. In the back, there’s a mattress on the floor, topped with piles of clothes and bedding. There are a few shelves, a couple chairs, some art propped up here and there.

Jeff and I both acquire an eclectic array of things through scavenging and salvaging sessions—[6] everything from used appliances and bicycles to light bulbs and nails, items that still have a life to live. Our spot functions as a sort of supply depot where others in our community can come to find recycled, repurposed solutions for the things they need, creating a form of function in a formless world.

Here, we make do without indoor plumbing, without stable electricity, and without easy access to water or bathrooms, so we alter our perspective to reinvent comfort in an environment most would consider unbearable. We manage needs in the moment, because the reality is we live, intimately, with uncertainty of what tomorrow will bring—whether that’s an arson fire, massive storms and flooding, or even our destruction. On any given day, the city could come to plow away our existence, and we couldn’t do much about it except embrace starting over. New discoveries, new horizons, a better tomorrow. We have to be optimistic or else we couldn’t survive.

Sometimes it feels like too much.

But when I light a fire and hear the wood crackling, some of that uncertainty goes up with the smoke, and my determination heats up with the coals. So every day, I build one. I create a tiny miracle out of almost nothing. I eat. I extinguish the blaze. And then, I’ve done something worthwhile.

Cooking is my act of hope.

Transitioning to life in the States wasn’t easy. Mom worked nights, cooking at a restaurant in downtown Oakland, and sewed prom dresses for teens in the neighborhood to fill the gaps. Dad, with his prestigious educational background, would ultimately work in I.T. at IBM, and get a second PhD in metaphysics from UCLA. But early on, he also worked jobs at the Arco gas station and as a cab driver. Every day, my parents were hopeful that the embargo would end, that relations between the two countries would be restored, and that we could return to our homeland.

Of course, things didn’t turn out that way. In the mid-‘80s, my family applied for citizenship, and we opened a delicatessen in downtown San Francisco to help us qualify. I remember Masoud and I going on the pickups with Mom and Dad in the early mornings—to the produce market, to the Cash n’ Carry, to the discount bakery, where we could buy day-old goods at half price.

My mom made the roast beef, the turkey breasts, and the tuna, chicken, and egg salads every night. When both our parents were working, Masoud and I would be in charge of boiling the eggs, seasoning the beef and getting it in the oven, checking it and rotating the pan. We learned to be fastidious: if we messed it up, it would be $25 down the drain, and wasting food wasn’t an option. My parents refused to be on government assistance, and that kept them, always, with multiple jobs. And when they weren’t working, they were usually doing something else productive.

My dad was always reading, building a library of some 2,000 books—none of them fiction because, he said, life was too short to not be learning something. When we took a rare trip to McDonald’s, he would make us earn it with math problems. When my parents later bought a home, he went to the local community college to get certifications to do the electrical wiring and plumbing himself. My mom, who was just 17 when I was born, dove into motherhood with enthusiasm, maintaining a huge vegetable and herb garden and cooking us dinner every night. We couldn’t miss it—my parents believed eating a meal together was a requirement to maintain our family bond. She would make fesenjoon, flavored with pomegranate paste and ground walnuts. Abgoosht, another stew with chicken or beef. Rice and tahdig at every meal.

To make a good flame, you need lots of fuel.

Pine wood pallets are in abundance around here, so I’ll haul them from local businesses and split them with a hatchet. I love splitting wood. It’s my physical workout, and it’s beautiful, too. Like eruptions of minerals to form crystals, redwood splits into perfect, smooth shards. You can see the age of the tree, the layering of the grain, the times when it was healthy and when it wasn’t, and all its knots along the way.

The process teaches me a lot. If I take two strikes at a piece of wood and it doesn’t split right, I don’t let it slow me down or stop me. I think to myself, that was a situation I couldn’t control, so I’m going to put it to the side and move on to the next. Because I shouldn’t deprive the other things in my life of attention. Because the next piece of wood will probably give me satisfaction. And if it doesn’t, I’ll just keep trying on.

In the years before I became homeless, I lost the ability to see the end result; to conceptualize why I was doing something, and what might come of it. In the midst of chaos and uncertainty, splitting wood, building a fire and cooking gives me clarity, a daily opportunity, with something I value, to see a complex series of actions to completion.

If the pan is slanted or uneven, you can leave parts of your dish uncooked. If the heat is too strong on one side, you can scorch it. So I set the planks at the proper angle, and judge where to put the pan. I tend the fire the whole time, add wood when it gets weak, and stir it if it gets too strong. The cause and effect is comforting; if I do everything just right, I’ll get the right result.

These are things that are in my control.

Growing up, spending money for the latest clothes and shoes wasn’t in the budget, so I started summer jobs at an ice cream parlor and a real estate company, afterward begging my parents to let me keep them during the school year. After graduating high school, I didn’t feel like the college environment was right for me. Instead, I got a job at the Hilton Hotel in the communications and hospitality departments, and moved to San Francisco, where I would live for 20 years. At 23, I landed my career job, doing outside sales for a janitorial supply company. I was 100 percent commission based, which meant if I didn’t sell, I didn’t eat, and it made me creatively determined, a self-starter, learning how to distinguish myself in a saturated industry by thinking outside the box. I would sit in traffic, look at the trucks around me, and start calling numbers.

“Hi!” I’d start. “I wanted to let you know that your truck drivers are doing a great job. And also, who is your purchasing agent?”

My father and I had a special kind of relationship, one where we could be straightforward when talking about business, but also sensitive about the emotions that it might entail. We called each other most mornings, and tried to meet for lunch when we could. When my parents decided to purchase a late-1800s multi-unit home where they would live and rent out units, it gave me an opportunity to invest with them and build equity.

Around the same time, I met Tony. We were inseparable from the start. A salesman himself, he was always traveling, but didn’t let that impact our relationship; for our first date, he was in Florida for a business trip, and flew back for just one night to take me out. I fell in love with him instantly, and the idea of marriage became exciting to me. Tony was a single dad, and after being so career-driven for so long, life in the suburbs with him and his son was attractive. I kept my apartment, but often stayed with him, taking a sabbatical from working while using my 401k to pay my San Francisco rent.

And then, one day, my nightmare came true.

On December 22, 2006, three days after I had celebrated my 33rd birthday with my parents, they were driving to Reno for a Persian concert event when a massive winter storm set in. They were traveling on the treacherous Donner Pass, a road that, unbeknownst to them, had been closed due to severe weather conditions.

Near the Nevada border, there was a winding turn, a curve so abrupt that shortly before, another car had spun out trying to adjust. A semi tow truck was blocking the road. My parents T-boned it, and it severed the top half of the car. My mom was killed instantly; my dad, who was paralyzed from the neck down, died in the hospital a couple of weeks later.

On Christmas Day, back in San Francisco, I was waiting for my mom to show up to help me cook a ham for dinner at my boss’ house. I tried to call, but it went straight to voicemail. On the 26th, I found my door pane covered in law enforcement business cards. Immediately I thought Masoud was in trouble. I was used to having business cards in my door, usually to inform me that he was in jail. Then I saw the cards from Nevada.

Tony called, because I couldn’t.

My parents—my best friends, my business partners, the bridge to my family back in Iran—all gone in one swoop. I knew then, my life would never be the same.

Sourcing food on Wood Street, like many things, is a patchwork; an exercise in existing off of what others cast away. Oakland has a number of free community fridges, and at any given time they might be stocked with prepared foods and freshly-picked items from community gardens. Local churches do food distribution several times a week. Some restaurants, like Horn Barbecue (where I got the mac n’ cheese), set unsold prepared foods outside for folks to pick up. I get a lot of my more unique items from curb alerts on Craigslist, from folks who are moving and need to empty their refrigerators, and from dumpster diving.

Actually, you can find some of the best ingredients that way. Brand new, undamaged goods like filet mignon, pre-marinated and ready to go—a variety of food I would have never been exposed to otherwise.

Waste is so typical that I’ve learned to tune in to its demographic patterns, creating an understanding of what might be available and when. The day after Christmas, instead of Christmas tree carcasses, I see TVs; there’s almost one to every home, as people are gifted new, shiny upgrades. Newlyweds put nearly everything in their kitchen out on the curb; knives that are still sharp; teflon pans without much wear. The diversity of items[15] that I come across is mind-blowing—everything from a hotel room sewing kit to a room’s entire furnishings.

My imagination goes wild thinking about how these items ended up where they’re at. Perhaps it was a bachelorette party that went too far and everything must go, even the carpet. Like, they don’t want to leave any trace of whatever wrongdoings happened here.

Sometimes folks in brand-new housing developments chide us for going through their trash, separating their cans and bottles and pulling out items of use. But which of us is displaying the greater disrespect? As a society, our eyes have gotten larger than our appetite; our consumption, greater than our resources. There will always be a level of waste, but we don’t have to cut down the forest for a toothpick. We shouldn’t butcher the cow for a one-time steak to lose a lifetime of milk.

Excess happens, but how we utilize the excess is what matters. Being on Wood Street helps me identify what’s truly important for my existence; what I need in order to survive.

When my parents got into the car accident, Masoud was in jail. He was in and out of jail most of his life—wrong people, wrong place, wrong time, wrong decisions. He was so smart from childhood; he could have done anything. But sometimes it was his intelligence that helped him find an easier, riskier path.

He was the only family I had left. I was spiraling from the grief of our parents’ death, and I needed his help—but suddenly, I had new, big tasks to manage on my own. I had to choose whether to take my dad off life support. I had to sort outstanding bills, to deal with the lawyers and create an estate. And then there was the property.

I took over management of their home, the 1800s apartment building we had invested in, thinking it a good way to make income while I sank further into depression. I did the math and told Masoud that we were basically set for life. Unfortunately, it didn’t go that way. Barely able to function, I had a hard time keeping the units filled. When Masoud got out of jail, he wanted to live there as the onsite manager.

“Good,” I told him. “Finally. I’m taking a break.”

I checked out almost completely. Tony and I had been on and off for years, and by that point, he had moved to Seattle. When other friends came to my door, I couldn’t answer. They started putting up missing persons signs.

Meanwhile, with Masoud struggling to reintegrate from his latest prison stint, the apartment building started to fall apart. The bills weren’t being paid and the garbage wasn’t being taken out. People were living there but no one paid rent, and it transformed, instead, into something I didn’t recognize. One day the police came. When they searched the units, they found a nine-year-old child with a broken neck, buried beneath two mattresses. The fire department boarded it up after that.

The place had sunk me. Everything I had went toward paying the mortgage. In 2011, when I got a notice that it would be put to public auction in three days, I started knocking on neighbors’ doors, and managed to sell it, cheap.

After I lost my place in San Francisco—the apartment I rented for 20 years—I moved in with Tony in West Oakland. At first, I kept myself going by getting involved with church fundraisers and holiday soup kitchens—helping other people was helping me not become the people that I was assisting. But after a while, Tony moved out, I took over the apartment and practically disappeared. I’d lay in bed, almost still, for days. Eventually I was evicted. I came home one day and found the locks changed.

I was done anyway. I was ready to give up. Wood Street was just a few blocks away.

The next step is to get your cooking fat hot.

It just depends on the day, what you have. Today it’s butter. But if I don’t have it, I’ll use oil. People drop off a lot of jars of peanut butter, and I’ll pour off the liquid at the top.

Living at Wood Street, I’ve learned a lot of valuable tricks.

When food is dropped off, I often separate the ingredients and try to stretch them into several meals. I’ll take the jalapeños off a sandwich, dice them up for a sauce. Dried cranberries in a salad might be used to make something sweet. If there’s meat, I’ll salt it like the frontiersmen used to do, so it stays good for longer. If the vegetables look bad, I’ll cut off the outer layers.

Then, it’s mostly about keeping it out of the sun and away from the flies and the rats, our nemeses. Sometimes I put food in a bag and hang it from the center of the ceiling. When I collect piles of wood, I’ll pour wax over it to preserve it from any moisture.

When I cook, I try to make big batches so if there are a lot of people around, everyone gets fed, or I can have leftovers. Ingredients will go through their natural stages. I make a lot of stews—as long as it gets to a boiling point every day, bacteria won’t build up on it. Eventually you can boil out the water, put the mixture on a tortilla or a piece of bread and it turns into a wrap. By the last day, maybe it will all be mashed together, fried up and become a fritter.

The creativity makes me feel like I’m still capable. It keeps my critical thinking going, it heightens my senses. That I substitute isn’t even the right term. I recreate, completely. From what is old and broken, I form something new. And it reminds me that I can be something new, too.

In June of 2019, I moved to Wood Street with nothing. In a way, I was running away from the constant reminders of my parents’ death—receiving paperwork in the mail, having forced conversations. Part of me wanted to just be free of it, whatever that meant.

It was a hard break. After getting locked out of my apartment, I climbed through a window to save my cat, but I didn’t take anything else, not even my purse. I dropped all ties with former friends. The only thing that connects me with my previous life is one gold bangle on my wrist that my mother gave me I was 17. And now Masoud.

When I became homeless, we had been estranged for 12 years, each unable to deal with the grief of losing our parents and filled with frustration from what had happened to the apartment building. But he was my only family left outside of Iran. I needed him.

I searched for Masoud across four Bay Area cities, trying to get some information about where he might be. I knew he had been unhoused in between stints of incarceration, and I checked all of his old stomping grounds in Richmond, El Cerito, Albany and Berkeley.

At Wood Street, I would tell people stories about him—this quiet charmer who built bikes and computers and was smarter than every person in most rooms. Sometimes people would say “I know someone like that, named Moose.”

Finally, someone brought that person here; a tall Persian with a beard who had just been released from Santa Rita jail, holding a bag of belongings. It was Masoud—Moose, a name he’d picked up along the way. It was the best day of my life. Having him at Wood Street reconnected me to my roots, to who I am, and to what really matters.

In February, he went to jail again, and I rely on cooking now more than ever. This is my therapeutic outlet, a way to process and find joy amidst so many challenges, a way to remain optimistic no matter what. When things seem like they’re falling apart, I can put them together again over the fire, and find a way to feel whole.

When the butter is hot, you put the yogurt mixture in the bottom of the pan.

It’ll start to bubble up after a few minutes, and that’s when I add the mac n’ cheese. I press it down to get rid of some of the air, and then watch it, checking the bottom every so often with a spatula.

The fat in the cheese gets all crispy, and the outer layer of macaroni basically becomes a crust. And then comes the moment of truth: the flip.

It should look kind of like a dome. You can cut it into slices, like a cake. It doesn’t taste quite like my childhood—its cheesier, fluffier, and you know, lacking the signature ingredient—but it gives me the thing I need right now.

Since living here, I’ve gotten back to the basics of life. You need shelter and water, you need love and compassion. It’s about keeping warm and dry. It’s about caring for yourself and for others at our most critical level of need: being fed.

I think that’s why even though I’ve been surrounded by food my whole life, I’ve found a new connection with cooking since I arrived at Wood Street. I could cook a recipe by the book somewhere indoors, and it would be a thing to do. Out here, it creates a different level of satisfaction, because it’s about existence. It’s about staying sane and finding meaning, about making space for creativity and grasping a perimeter of control. It’s about survival, in every sense of the word.

The pain that caused me to become homeless, I still haven’t cured it. The wounds are still open, even 13 years later. But I don’t feel hopeless anymore. I feel malleable. I move through the world again. I get up out of bed. I make jokes. I hug friends. I carry on.

Still, I’m not the old me. Like the perfect cookbook recipe, she is gone. I don’t have access to all the ingredients anymore, and I can’t take their inflexibility seriously. And that’s OK. I can be a different me—a recreation, a repurposed work of art. I can be a redwood, split down the middle and still coming out smooth; a near-miracle, an act of hope in my very existence.

I can be tahdig with mac n’ cheese.