"Your Struggle is My Struggle"

How the children of meatpacking plant workers sparked a movement

By Anikah Shaokat / Photos by Dulce Castañeda

Back in April, we began hearing horror stories about Covid-19 running rampant through the country’s meatpacking plants.

The impact of COVID-19 is ongoing and ever-changing, revealing new repercussions almost daily. But since the onset, meatpacking plants and their workers have been hit very hard. As the pandemic took hold, plants across the country continued business as usual without implementing proper sanitation and safety measures to protect their workers — despite rising case counts. In fact, some even sped up production, warning the nation of an impending food shortage. On April 27, just one day before President Trump signed an executive order to keep meat processing plants operating, the Center for Disease Control reported that over 5,000 plant workers in 19 states had tested positive for the virus. The order was “to ensure a continued supply of protein for Americans.” But the burden to keep the nation fed during a pandemic has been borne by thousands of meatpacking plant workers, and according to the Center for Economic and Policy Research, over half of these workers are immigrants and refugees.

Plant workers have been deemed essential, but treated as expendable, says Dulce Castañeda. Her father has worked for Smithfield Foods processing plant in Crete, Nebraska, for 25 years. In April, several of his co-workers tested positive for the virus — one of whom worked next to him on the line. The company’s response to the spread was rudimentary at best. “Instead of a proper mask, my father received a hairnet to wear over his face,” says Dulce. Rather than plexiglass dividers, the company set up cardboard barriers between lunch tables at the cafeteria. Operations at meatpacking plants make it nearly impossible to maintain social distancing protocols. “The production lines move really fast, so workers are often standing very close to each other,” says Dulce. Moreover, breaking down and deboning an animal, her father’s primary job, is a laborious task that can make it difficult to breathe under a mask.

The company’s lack of transparency intensified the workers’ vulnerability and fear. “My father and his coworkers got very little information about contact tracing and the number of positive cases in the plant,” says Dulce. Furthermore, unclear time off and sick leave policies contributed to the heightened sense of tension among workers. “Workers didn’t know if they were allowed to take time off, and if they would get their sick pay if they stayed home.” According to Dulce, information about changes to these policies were primarily communicated verbally. “And if it was written, it was all in English.” Consequently, plant workers felt lost and frenzied, afraid to speak up in fear of retribution.

But their children are now organizing on their behalf, demanding better, safer lives for their parents. In March, Dulce found a Facebook group with several other adult children of plant workers, many she recognized as neighbors and acquaintances. “Crete is a very small town, and Smithfield is the largest employer here, so everyone in this group knew each other in some capacity.” Connected online, the young adults shared concerns their family members had kept quiet. “The world’s largest pork producer has been grossly mishandling the spread of the virus inside their plants across the country,” Dulce says. “They were toying with our parents’ livelihoods, and our parents were afraid to speak up in fear of retaliation. So we decided to channel our anger into action.” Their collective rage spurred the creation of Children of Smithfield, an advocacy group fighting for better working conditions, proper PPE, guaranteed hazard pay, and protected paid sick leave. “For us, it's a two-way street. Our parents came to this country to give us a better life, and we want the same for them,” says Dulce. “We’re now young professionals who have all this upward mobility and access to resources, yet our parents are still working at these hazardous jobs. They deserve better.”

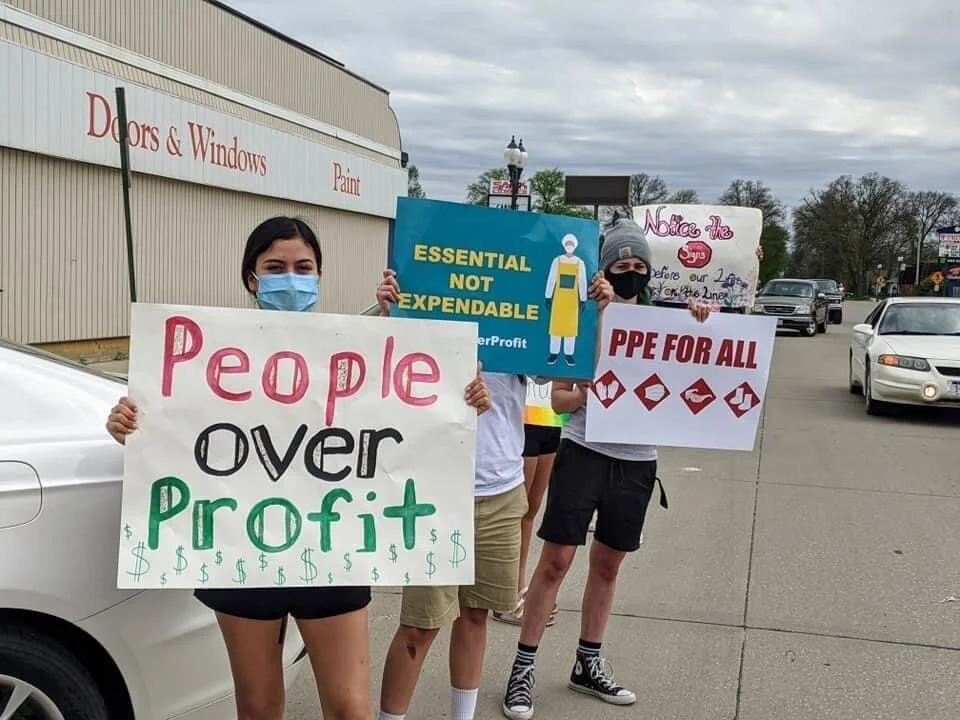

Seeking to expand its political reach and effectiveness, Children of Smithfield has joined forces with Solidarity with Packing Plant Workers, a statewide organizing group, as well as ACLU of Nebraska. They’ve pushed online petitions demanding basic protections for meatpacking workers. They’ve organized drive-in protests at the gates of several meat processing facilities. And with the support of Senator Tony Vargas of the South Omaha District, they’ve fought to implement enforceable safety regulations across the meatpacking industry.

At first, the goals of Children of Smithfield were simple. “We just wanted to share our stories and raise public consciousness so people would recognize this as a serious problem,” says Dulce. As the group gained attention and support, Smithfield’s PR machine pushed back, insisting the company had taken necessary actions to ensure the safety of their employees. Dulce and her fellow advocates weren’t having it. “We sent a letter to the editor of Crete News, a local newspaper, explaining the real situation inside the plant and why we are deciding to speak up on behalf of our parents,” says Dulce. She notes that the group was intentional in choosing Crete News. “We knew that the majority of their readers are generally older, white Nebraskans who may not have the opportunity to hear the personal stories of plant workers. And it was important that our message reached a broad range of audiences.”

The letter accomplished just that. Hundreds of people participated in a protest at the gates of Smithfield. “We even saw some elementary school students holding up signs,” Dulce says. “It was really incredible to see these young kids there. They may not completely understand what was going on, but they knew something wasn’t right.”

Political advocacy is just one way Children of Smithfield is helping the local community. It also serves as a resource for critical information. “We had folks reach out to us because their parents were having issues getting their sick pay from Smithfield,” says Dulce. “We were able to connect them to union officials who could help.” The group also takes pride in championing the voices of young children whose parents are putting their lives at risk to support their families. “We felt a responsibility to speak on behalf of these kids who don’t fully understand the situation,” she says. “We are all mostly in our late teens, 20s and 30s. We can survive on our own, but the livelihoods of these children depend on their working parents.” Smithfield officials were quick to label them as “activists with an agenda.” To Dulce, their only agenda was to protect their loved ones and their community.

The attention from national media came as a surprise to the Children of Smithfield. “I don’t know if any of us thought this would turn into a movement,” says Dulce. “[Especially because] at the beginning, we didn’t really know where to start.” But organizations across the state were eager to help. Nebraska Appleseed, a social justice nonprofit organization, provided them with valuable guidance for developing effective advocacy strategies. “They told us that the worst thing we could do is not do anything.”

Even before she began her journey with Children of Smithfield, Dulce had the spirit of an advocate. “I’ve been involved in volunteer work since elementary school, and even in college, I was quite active in social justice protests,” she says. “I’ve always felt the urge to stand up for what’s right.” She attributes her altruistic nature to her parents, who instilled the importance of helping those in need. “They led by example,” she says. “My dad will take the shirt off his back and give it to someone else.”

But she never thought that her hometown of 7,000 people would be the epicenter of a national movement. Battling the injustices that endanger her parents, her neighbors, and her entire community has revealed the powerful social and political forces around her. “I feel like we go about life without thinking about it, but local government, local codes, state laws, federal laws — all of those things affect us every day,” she says. Her advocacy has also enlivened her family’s dinner table conversations. “My father and I spend hours talking about how things could change, not just for our community, but for all immigrant communities across the country.”

Dulce’s involvement with Children of Smithfield has cemented her commitment to transforming America’s industrialized food system and advocating on behalf of workers. “It’s taught me a lot about union history, the labor movement, and how it has all been weakened through corporate lobbyists over the past decade.” She notes that the experience has made her think more critically about food and how it gets to the table. “Before a meal, my family always says grace. Of course, to give thanks for the food that’s on the table, but to also give thanks to the hands who helped put it there.” She hopes that the future of food will protect those hands—the hands that are deemed essential to keep this nation fed, that belong to humans, essential to the lives of their loved ones.

To support the Children of Smithfield, make a donation here.

The title, “Your Struggle is My Struggle,” is from a speech that one of the Children of Smithfield gave during a protest at the meatpacking plant.